Jenny Shen

Primary Development

Jenny Shen, one of three founding partners at Primary, a New York City-based designer-development firm, sees every new project site as an opportunity to set new trends. Working with her team on infill projects across New York, Boston, and Houston, Shen is helping define the design-development model as a nimble alternative to traditional development.

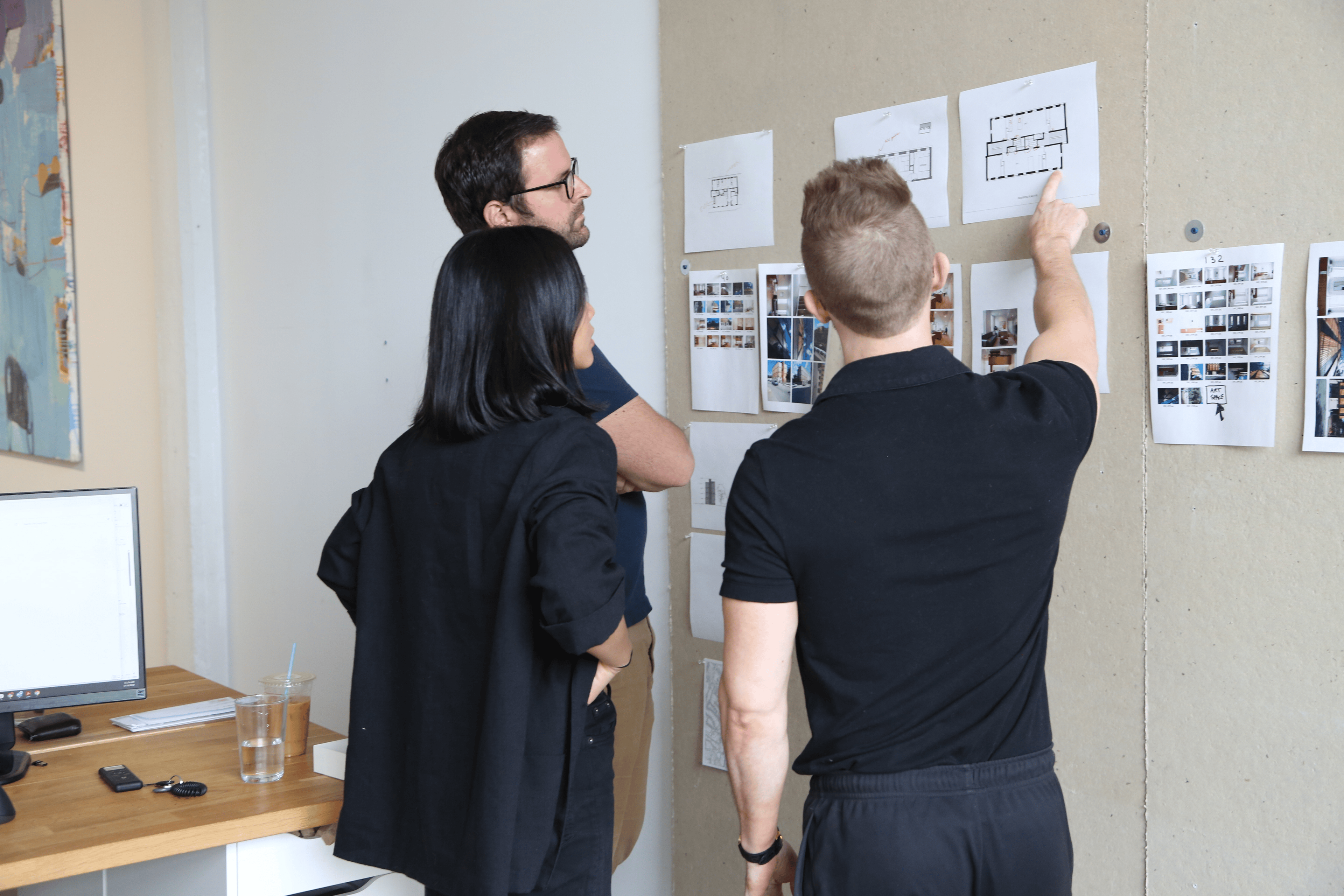

PRIMARY PARTNERS (FROM LEFT TO RIGHT) STEVEN MEYER, JENNY SHEN, WYATT KOMARIN IN THEIR BROOKLYN OFFICE.

PHOTO BY EVAGRIA SERGEEVA FOR COMMONPLACE.

What types of projects do you work on? What defines your approach to development?

I'm one of three founding partners of Primary. We are designers and developers specifically trained as architects who got into development as a way to have more agency. When you work at an architecture firm, you are given very narrow constraints of a problem to solve without the capacity to consider whether the right questions were asked to begin with. By the time the brief is on your plate, many of the answers have already been provided and sometimes they aren't the right ones, in my opinion. My partners and I thought we could be more impactful if we were there to ask the right questions from the start and the best way to do that is to develop our own projects.

At Primary, our architecture and design background is where our strength lies. As problem solvers, creative thinkers, and strategists, we're great at assessing the big picture and challenging the right assumptions. We primarily develop multifamily, single-family, mixed income, and affordable housing, but there is no standard off the shelf, highest and best use when we're starting with a new site. Instead, we ask: what is the most worthwhile problem for us to tackle?

Besides development, we also provide consulting services in areas like entitlements, design-oriented feasibility, and project strategy. We see these engagements as a way to apply our design philosophy and creative problem solving, without necessarily waiting years for a project to be completed.

PRIMARY PARTNERS JENNY SHEN, WYATT KOMARIN, AND STEVEN MEYER IN THEIR BROOKLYN, NY OFFICE

Does Primary’s emphasis on design-focused development make it challenging to secure project financing?

Yes and no. We are never the only actors and stakeholders in our projects; we partner with equity investors and typically use traditional financing, so our projects have to be financially feasible as well as innovative.

However, we've learned over the years that we shouldn't compete for projects where the best answer is a standard box. In those kinds of projects, buildings are designed in Excel and we can't play to our strengths. Instead, the ideal site or project for us is one in which the best solution cannot be delivered by a typical developer; a site or condition that's challenging enough to require our strategic design solutions on one hand, but which simultaneously has enough meat on the bones for an investor who might only be concerned about returns.

That said, our capital stacks have been relatively straightforward so far. For our market rate single and multifamily projects, it's been one equity investor and one lender, with us as the developer or, in some cases, the development consultant. For the affordable projects we're also working with the city and with an alphabet soup of funding sources, so you have to really get creative with applying here and there. Specifically we leverage the Community Preservation Act* in Boston, which has been great for us because it has fewer requirements that would affect the actual spatial attributes of the building. Other sources of funding for affordable housing will set really specific definitions, like for the size of the bedroom or closet, as well as affordability requirements, some of which compete with each other.

We haven't kicked off a project with a complex capital stack yet, but that might be next on the horizon. As the world moves past the pandemic and the market calms down a bit, we're looking to broaden our network and work with new partners who believe in our approach to development. Right now, I think the perception is just that we're the new kids on the block, but that undervalues us as qualified developers and architects bringing fresh ideas to an industry that mostly favors what has been done before. Our projects have been pretty successful so far, and we're eager to continue proving out our thesis through both short-term consulting engagements and long-term development projects.

* The Community Preservation Act (CPA) is a Massachusetts state law that allows cities and towns to create a dedicated fund for affordable housing, historic preservation, and open space and recreation projects. The fund is financed through a surcharge on local property taxes and matching funds from the state.

7-11 HAYNES STREET TOWNHOUSES PROJECT IN BOSTON, MA

BY PRIMARY.

INTERIOR OF 40 TERRACE STREET PROJECT IN BOSTON, MA

BY PRIMARY.

What led you to architecture and development?

Growing up in Ohio, I was a really nerdy kid who loved to draw, so when I went to Columbia for my undergraduate degree, I studied fine arts and economics. I eventually fell into architecture by accident through a series of classes that went well. Architecture and development really is a bit of both art and econ, so I guess the interest was always there. After I graduated, I worked at Bjarke Ingels Group for two years before I went to Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) for my graduate degree. That's where I got lucky and met a few really great like-minded friends who are now my partners.

My partner, Wyatt Komarin, worked with our investor on the first acquisition when we were still students at the GSD. They found a parcel of land which was later subdivided for development as three single family townhouses. Wyatt basically ran that project from his studio desk at school. Then we got involved in some RFP competitions in the city together as students, alongside our other partner, Steve Meyer.

Boston, like most major urban areas, essentially has only infill sites left to develop, so you never get a blank slate of land. You always have context and the context is always different. Moreover, the zoning in Boston is extremely challenging and almost anything requires an entitlement or community process. So you're dealing with both unique physical site constraints as well as unique political, and often one-on-one neighbor-to-neighbor, relationships. That means that pretty much every site requires a unique solution. We thought: how can we take these challenges and turn them into opportunities for unique buildings? There's no reason that all new buildings should be traditional triple-deckers.

My partners and I worked together informally on these projects until we graduated, moved back to New York and formed an LLC. In late 2018, we rented an office space and committed to doing this full time.

What does impact (in real estate) mean to you?

At a basic level, we believe that caring about the community is what makes a neighborhood great. The general message we try to send is that we care about the urban environment and aspire to make it better. We want to make the ordinary person walking down the street feel glad to see something that wasn't there before. For the building's inhabitants, we want them to be surprised by the variety and richness of the space when they were perhaps expecting just a shoebox.

To achieve that requires design decisions that can't be captured by an Excel sheet and a financial model. Minor choices, like how materials are blended together or how rooms interact, can have a huge impact on a person's everyday life. By extension, those choices will influence their desire to take care of their home and their neighborhood, which all factors into making a neighborhood a better and more desirable place to live. It all starts with caring about what gets put there in the first place.

For example, we're in the early stages of some single family housing projects in Houston. It's urban infill, but the product is single family in a pre-existing urban grid. Our goal is to raise the standard for housing by seeing if we can move away from cookie cutter boxes, introduce some special richness in our designs, and see how the market responds. If we do that and it works, then that will go a long way in showing that it's possible to be more thoughtful about how projects are designed.

The biggest compliment that we ever got was from a total stranger who photographed one of our buildings at night, found us online, and sent us a message just to tell us that it was great. Or when another guy, a designer, snapped a photo of our work on Instagram with the caption: “I guess architecture still can happen.”

JENNY SHEN BY DAVID DEGNER FOR COMMONPLACE.

INTERIOR OF THE 7-11 HAYNES STREET TOWNHOUSES PROJECT IN BOSTON

BY PRIMARY.

How does your idea of impact translate into your work?

Typically, a developer will partner with an architect, and the developer will bring capital and maybe some local political clout. The architect is providing the design, but there's no symbiotic relationship. This becomes difficult when there are more stakeholders involved, which inevitably happens when it comes to dealing with the city and the public. You'll often end up negotiating with different community groups where the only solution is through adjusting the design.

We found that being fully involved in a project on both the architectural and development sides from the beginning allows us to be nimble and adapt to asks that can sometimes be really challenging or unexpected. Our most successful execution of that idea is another project called 3326 Washington Street. There we went out and had a community meeting before we even started the design process and got to know the community's preferences both for the fundamentals of the project's program, as well as its appearance.

“We came out multiple times over the course of a year and were able to listen to people's thoughts and design strategically to address a diverse range of stakeholder concerns. You can accomplish a lot with that kind of empathy in the negotiation process.”

VISUALIZATION OF 3326 WASHINGTON STREET MULTIFAMILY PROJECT IN BOSTON, MA

BY PRIMARY.

How do you think about the tension between immediate financial returns and impact?

That's pretty much always something you have to negotiate. In the acquisition phase when you're just trying to convince people to work with you, you want to pitch a unique design - something innovative - but your project still has to work under normal development expectations or other people's return measures. Just as homebuyers have gatekeepers acting as middlemen to their purchase, we have to deal with some kind of middlemen: appraisers and other gatekeepers who are not interested in the narrative of your project. They are the ones who set the dollar value of what you're proposing, and by extension the amount of financing you can get, and then you just have to work with that. There's an art to figuring out creative, representational styles or arguments to make a proposition for people who are specifically not supposed to care about the design.

And, even after the equity is raised, we, as an individual company, have extremely limited control over the tides of local markets and the broader economy through the lifecycle of the project. Our current economic climate is very difficult to work in, but, even if our proposition is a unique design solution, we're still evaluated under the same criteria as other developers and by how our projects perform on a pro forma. For example, we started a project in January of 2020 which is just finishing now, and it's gone through so many different iterations due to what's going on in the market and with COVID. The project still has to make sense through all of that.

“So the way we respond as designers is to really define that which is irreducible — what is the fundamental design component as opposed to just the fancy detailing. That's where we really want to focus our energy because that will survive all the cycles and iterations that a building will see.”

JENNY IN FRONT OF PRIMARY’S 40 TERRACE STREET MULTIFAMILY PROJECT IN BOSTON, MA.

PHOTO BY DAVID DEGNER FOR COMMONPLACE.

Is there a project in particular that you think is a great representation of your approach?

We've only been in operation for a very short period, much of which was hindered by the pandemic, but as of the last two months we are finishing up three projects along Terrace Street in Boston. They are very close to subway stations, but in an area that has been historically miss-zoned and, for that reason, underdeveloped. What you have there now is this hodgepodge of small single family houses and industrial warehouses in different states of use, with a strong local artist community.

But there's a desperate need for housing in the area, so we acquired two plots of land via a city RFP process, acquired another through a standard market repurchase, and developed them one after the other. Two of those are now 100% affordable and artist-housing apartments and the other is a mixed use building with studio spaces and condos on top. They're all successful in different ways. Each enriches the street in a different way.

Previously, the street was kind of a pass-through zone with a sort of rugged industrial character and very little foot traffic. There were a lot of traffic accidents because of cars zooming by without the pedestrian activity to anchor the street as a destination. Now, one of our buildings at Terrace is more of a neighborhood icon, with a beautiful facade that speaks to the industrial heritage and character of the street, and the two affordable buildings have studio spaces on the ground floor. We're hoping that once these buildings are fully occupied, there will be more activity on the street and more pride for the place that shows it's not somewhere to just pass through. Delivering three buildings at one time helps reinforce that and encourages other developers to look at other nearby lots. I know a lot of them are in the process of being entitled now.

FACADE OF 80 TERRACE STREET PROJECT IN BOSTON, MA

PHOTO BY DEVID DEGNER FOR COMMONPLACE

What are the main challenges for your business today?

Having productive conversations with the community is the great challenge for development, especially in urban areas. Private development starts off as the bogeyman, which means you're approaching the community with a conversation that's already set up to be adversarial. That makes it very difficult to talk about the merits of a project and to genuinely consider its pros and cons in a productive way. We've run up against this challenge in every project and it's tough because every community has different priorities. And then “community” is not some sort of monolithic mass, right? It's many individuals with different, and sometimes competing, priorities. So I would say that the design-development model is a good way to juggle this, but at the same time it remains a challenge.

The entitlements process can also be a major challenge. It's notoriously difficult in Boston and that mirrors a lot of other cities, New York included. Every project basically requires a rezoning and every rezoning requires an extensive committee process. There's a lot of uncertainty every step of the way and policy requirements are constantly changing. The community will also always ask for more on top of the basic requirements, which can hold the process up further. Keep in mind, as a developer, every day that you are delayed is another day that you are burning cash. That translates into a high level of risk, and that high risk is borne in very volatile land prices. In the long run that means very few development starts, and that many more projects are entitled than get built.

In another neighborhood we've worked in, Jamaica Plain, you see tons and tons of projects showing up at the community process stage, but never getting off the ground. Often that's because the market changes and pulls the rug from under your feet. For example, you complete a negotiation with the city, and commit to a specific program mix and affordability level. Then suddenly the conditions change and you'll have to ask yourself: do I back out, go through another year of the process, and carry the cost of that? Or should I just take a loss and abandon the projects?

"What everyone needs is a little bit more certainty at the starting line, so that there's not so much risk borne by the individual."

JENNY SHEN, PHOTO BY DAVID DEGNER FOR COMMONPLACE.

PRIMARY PARTNERS IN THEIR BROOKLYN, NY OFFICE.

PHOTO BY EVAGRIA SERGEEVA FOR COMMONPLACE.

Who inspires you? And who has helped you along the way as you've shaped your career?

One of our recent office trips was to Paul Rudolph's townhouse in Manhattan and it was extremely inspiring. It's always amazing to see people take “boring” types of buildings and produce something extremely interesting out of them. Hertzog and De Meuron are good examples as well. They do a lot of commercial work, but every building feels very bespoke and they're actually taking on new challenges in every project; in some projects they'll even experiment with different material types.

On a more personal level, both Wyatt and I worked at a company called Alloy, which is a design developer. They set the highest standards for design development for themselves and have achieved a really balanced and happy workplace. The founders, Jared Della Valle and AJ Pires, have been mentors to us, and they've also produced a network of alumni that have all gone on to become creative entrepreneurs themselves in the real estate development space or adjacent. My last architecture job, at Bjarke Ingels Group, also showed me that one can do some very interesting things with otherwise typical development projects. That's the same attitude we want to bring to our projects.

Besides the amazing people who have guided me in my career, I've met some really inspirational women as an amateur boxer. Development and business can sometimes feel unfair because many of your competitors may have a starting advantage. The world of boxing, on the other hand, is filled with people from underprivileged backgrounds who are quite literally fighting for their place. The women I box with all worked their tail off to be there and I have an immense amount of respect for them as training partners and competitors.

In fact, I would say boxing in general has been very helpful in my career. Development is a man's world - I've seen maybe one other woman on a construction site - and boxing has helped me build my confidence and carry myself a little taller in the workplace. It's also great to be able to vent the stress from the lack of control one has over development; you can just take it out on the punching bag. And there are aspects of strategy, like knowing where and when to apply pressure smartly, how to pace yourself over a long period, or how to keep a level head in the face of uncertainty. All of those things are important to being a successful developer, but instead of being stretched out over several years it's all condensed into three rounds in the ring.

What legacy do you hope to leave?

We as people don't have control over how we are perceived in the long run and we can't control how our buildings will look over generations, but we aspire to be sort of indirect trendsetters. Our thinking is that a successful project is one that helps foster a community where there wasn't one before or, at the very least, raises the standard for design excellence and the typology in a community. You could have single family houses or condos that are just throwaways, but if you introduce something really beautiful, really special — and it sells — then more developers beyond us will be challenged to meet those standards.

Jenny Shen

Primary Development