Matthew Temkin

Greatwater Opportunity Capital

As Detroit continues to grapple with disinvestment and affordable housing availability, Matt Temkin and Greatwater Opportunity Capital are stepping up to the plate with neighborhood investments focused on historical preservation and attainable housing.

MATTHEW TEMKIN AT GREATWATER OPPORTUNITY CAPITAL HEADQUARTERS IN DETROIT.

NICK HAGEN FOR COMMONPLACE.

What defines your unique approach?

We've been working in Detroit for almost nine years, and our approach has been the same since the start. There were two waves of construction in Detroit, in the 20s and 50s, and we focus on re-developing apartments from those two eras

My first project was a 26-unit apartment building, all 1-bedrooms, built in 1925. It was the type of building that had not seen investment for ages, with people who lived there for decades and remembered when it was nicer. But these apartments are pretty amazing. They had all the original floors, baths, woodwork, and it's not like the building was built for wealthy people, it's just the quality of the work and materials from that time. Our approach has been to keep what we can. Cool old cabinets and 100-year old floors, we'll refinish them, we're not taking them out if we can avoid it. It doesn't make sense to pay to remove these materials that I couldn't afford to reinstall today, or swap them out for materials that aren't nearly as good.

The rents in Detroit aren't that high and if you look at the cost of construction relative to rents, it's challenging. But our approach of keeping historical elements like old floors means we can renovate more affordably, and thereby rent to people at more affordable prices, like $800 a month. So with these apartments, it's cheaper to renovate, it looks better, people like it more. The tenants that have lived there forever are happy that suddenly the lights are working and that they can count on the boiler — all at affordable rents. If you came out to visit, we might look a bit like a one-trick pony, because all the projects are apartments renovated with the same playbook.

BY NICK HAGEN FOR COMMONPLACE.

What financial criteria should your projects satisfy?

I'd say it's about making choices that lead to the optimal balance between the experience for residents, and deals actually working. Of course, if the deals don't work, if they don't make money, then we can't do what we're doing. We're largely offering apartments at prices below what the government would pay us for them through Section 8 vouchers, while still making returns that are attractive to our investors.

Something like 97 or 98% of our apartments are affordable at 80% AMI and over half are affordable at 60% AMI, so we really feel like we're offering value to residents by providing housing that feels like a good value to them. We walk that fine line on the investment side of things, and are intentional in not really pushing the gas so much. Part of it too is that it's just good business, because not having a ton of turnover is accretive to returns. It's like, could we be getting an extra $50 or something? Yeah, maybe. Would it lead to an extra 10% of turnover? Also, maybe.

Tell me about the path that led you here?

I started out flying to Detroit once a month from New York City, walking around the streets to get a feel for them. On the surface Detroit is this huge place that has experienced a massive decline in population — then tax base declines, rising crime, disinvestment, all of that — so it's not all going to simultaneously just lift up. But there are areas that will lift. The downtown for example has been lifted by a lot of investment from Dan Gilbert.

I realized it's a huge city, an awesome city, with many neighborhoods that will change, with more people moving in than out. I landed on one of those apartments on the East Side in The Villages, which is a collection of a few different neighborhoods — like the West Village, Indian Village, East Village — about three miles east of downtown. You've got these unbelievable custom-built Indian Village mansions that are 100 years old, constructed when Detroit was just printing cash, right next to these apartment buildings that were once inhabited by the same working people who built those mansions next door. There's also single-family homes that exist in different sizes there, so a great mix of housing types and incomes in that neighborhood. So I made it my focus and just tried to figure out what to do.

Over time, my partners and I found out that it was all about hitting a sweet spot: projects too big for one person and too small for private equity, in the $5-10 million range. So that's really what we've done over the years and how we've scaled. Our most recent project was a $25 million deal. At a certain point we realized, ok, there's something to do here, we need to actually stand up a company and be able to hire people. So we did that in the wake of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and the creation of Opportunity Zones, which were basically where we had been working the entire time anyway.

EL TOVAR APARTMENTS, ORIGINALLY BUILT IN 1928, UNDERGOING RENOVATION BY GREATWATER OPPORTUNITY CAPITAL.

VISTING 9226 KERCHEVAL

PHOTO BY NICK HAGEN FOR COMMONPLACE

What drives you and motivates you to do what you do?

You can probably tell that I have a particular love and interest for old buildings. For about five years after our first investment, I slept in the basement of one of these buildings, next to the boiler. It was actually really nice — incredible tilework, original wood floors, beautiful terrazzo in basement hallways. I like what it means to build here, preserving these cool old buildings, you know?

But also I like the story of Detroit and what it means nationally. America can't be this place where you've got five wealthy cities and then everyone else is poor. The story for a long time has been about the concentration of capital in New York, California, DC, Boston, and Miami. Whereas I think historically there have been many more options regionally, especially in the Midwest. If you grew up in the sticks in Indiana, you could move to Gary, and if you got too big for Gary, you could move to Indianapolis, and if you got too big for Indianapolis, you moved to Detroit, and then to Chicago and on and on. There needs to be the ability to advance, and what's so important about places like Detroit, is that they are rungs on that ladder of mobility.

HEATHER HALL LOBBY, BUILT IN 1920S AND RENOVATED BY GREATWATER, PHOTO COURTESY OF GREATWATER OPPORTUNITY CAPITAL.

What does impact in real estate mean to you?

There needs to be more housing nationally, and housing costs are through the roof because there's not enough of it. This is a very clear driving force behind our work. We're working on a problem that is big locally and big nationally and our focus is to renovate intelligently and rent affordably.

At the same time, this is a problem that is also big individually. By providing fine architectural details and quality materials, you can give people a real sense of value. And that's really important because this is people's housing, you know? It's where they live and come home to at the end of the day. So if it feels like a good value to them and it feels like a nice place to live, then that has to count for something, right?

Of your projects, which do you think is the most impactful?

I would actually say it's the first project we ever did, the 26-unit one we talked about. Because that's where we discovered our basic business model: that we could leverage these particular building types to provide mostly affordable housing, while delivering real returns to investors and real value to residents. That we could renovate apartments that were a joy to live in, in neighborhoods that were beautiful, and for not that much money — all while including the historical detail that I love: things like ornate plaster, terracotta, and marble finishes, high ceilings, and large windows for ample natural light.

MATT TEMKIN AT 9226 KERCHEVAL

PHOTO BY NICK HAGEN FOR COMMONPLACE

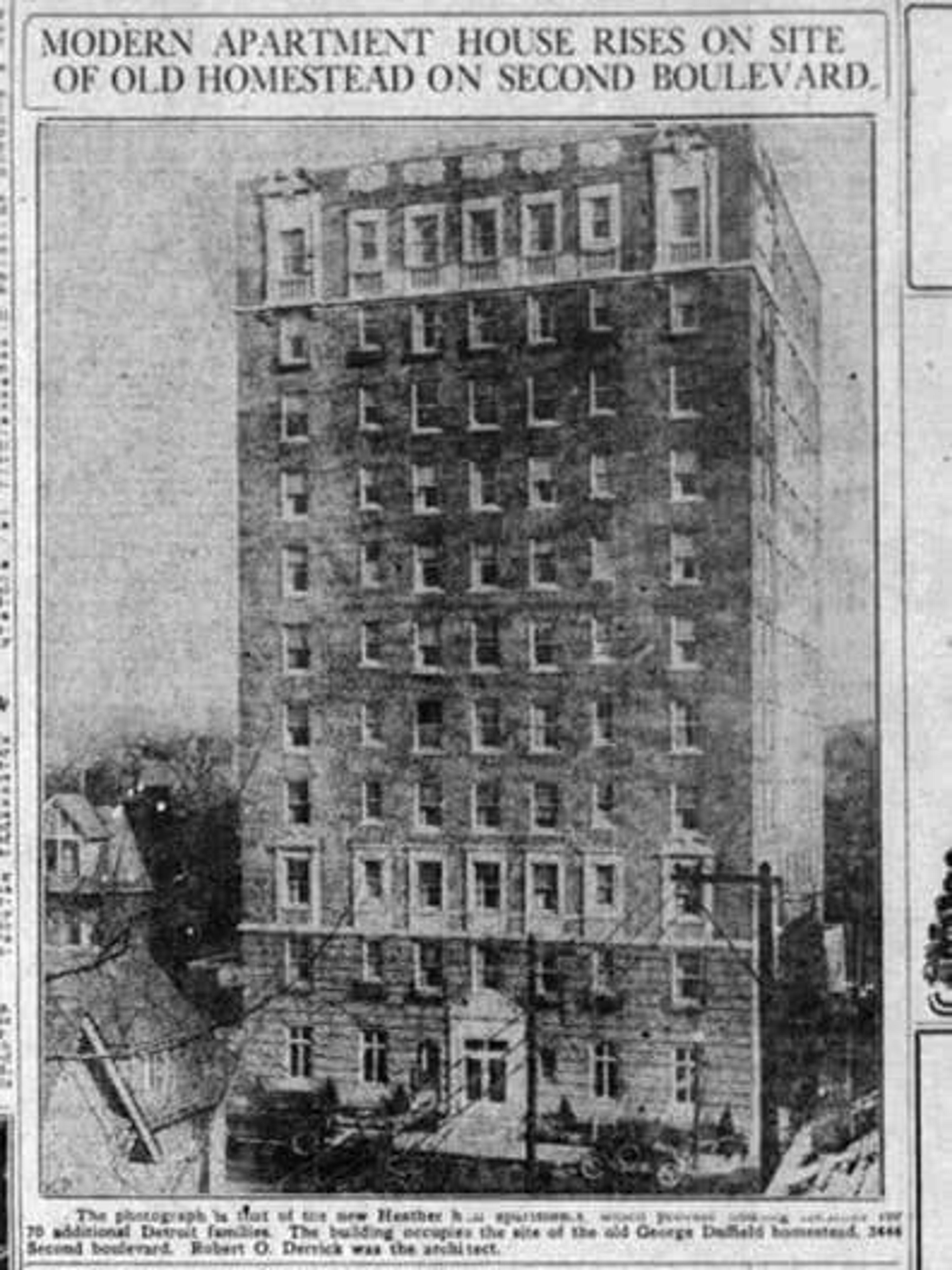

HEATHER HALL, DESIGNED BY BROWN + DERRICK IN ITALIAN RENAISSANCE STYLE AND CONSTRUCTED IN 1920S.

What challenges did you face? What were the unique challenges in financing projects?

There's not a robust lending market in Detroit. For a healthy real estate development market, there needs to be more local banks. You can get Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac* to lend on a stabilized project, but there's not a lot of upfront lending on acquisitions or construction. I get the sense that it's happening more in the suburbs, but not so much in the city itself. Many lenders would rather not risk having to take over an asset here. So stabilized financing is not an issue, but acquisition financing or construction financing — those things are tough.

The equity side of things is better. We're able to work with the full gamut from institutional partners, family offices, to high-net-worth individuals. As the projects have gotten bigger, we've done a joint venture and we're doing another one. We're ready to partner with individual investors all the way up to the institutional level.

Then there's the more general challenge of costs. Construction costs going up dramatically over the last several years hasn't helped, and that becomes a real problem because sometimes the buildings might look similar, but they're not the same. When you're buying and rehabbing an old building, you don't really know what you're getting behind the walls. Also, from an acquisitions perspective in the last 12 months, interest rates have doubled. What that means is your building is worth less than you think it's worth, and people haven't adjusted yet.

Taxes in Detroit are also a genuine issue. The city used to have two million people in it, and the physical size of the city reflects it. Municipal services still need to cover the same infrastructure footprint, but with a much smaller population of 600,000 and its smaller tax base. So property taxes are devastating and have gotten a lot worse since we started. But there are solutions on the horizon and I'm optimistic. Nobody wants Detroit to be an area of economic concern any longer, but a place where people can develop and do business.

* Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) are government-sponsored enterprises that exist to provide stability and liquidity to the U.S. housing market by purchasing and securitizing mortgages from lenders.

HEATHER HALL BY NICK HAGEN FOR COMMONPLACE.

How did you approach solving those problems?

It's important to give people looking into Detroit a sense of opportunity, of the economic importance of the city and its trajectory. That's the point of my bus tours around the city. I was reading something recently about India's economy that could apply to Detroit: it somehow manages to disappoint both the pessimists and optimists. Every two years you hear: Detroit is on the ascendance, it's a place to be. But then if you actually went to visit it, there would be one new coffee shop. You felt that real development was not happening.

It was bound to disappoint the optimist, but also managed to disappoint the pessimist, because, look: there is a gradual accumulation of those things over the years, that coffee shop did open and it's still open and has settled in. Another opens this year, and the next. Drive around for a bit and you will see somebody who is opening up a flower shop in a place where you didn't realize there were human beings. And then you're like, okay, that's kind of cool.

That's the idea behind my bus tours: to give people a realistic view of the good parts and the tough parts while demonstrating opportunity. Detroit is a long term play. For people on the equity side of things, if you're thinking about a good long term investment, Detroit is for you. And that's everyone we work with.

BY NICK HAGEN FOR COMMONPLACE.

Who inspires you, or has helped you get this far?

I read Sam Zell's book, Am I Being Too Subtle?, and really loved it and was inspired by it. The way that he thinks about everything I think is interesting. He called himself a serial opportunist, and I think that's what a lot of real estate is. For our business the thought process might be something like, “okay, we've been buying apartment buildings, but there's not been any new construction of single family homes in Detroit. Is there an opportunity for us to maybe offer somebody the ability to step into that?” They can rent the studio from us for $600 to start, but they can move up to a one bedroom eventually. And then one day it might be: “hey, look, instead of a lease renewal this year, do you want to buy a house? We can build you one.” Just an example, but the idea is to be looking for opportunities to give people something they might want.

Then there's Ethan Orley, who is a hotel guy originally from Detroit that I worked with for years. Before I did any of this, I was selling him on the idea of returning to do commercial development in Detroit. Eventually he said, “It looks like you really love Detroit, maybe you should do this.” And I thought about it for a bit and realized he was right; I really learned a lot from him.

But really I think the people that inspire me the most, honestly, are the people that are here making it work in our neighborhoods — those that are here making their community garden nicer, or the family renovating that house on that block where nobody else is caring for their house. Nothing is more influential or important to me than what those people are doing because that's how you can see that Detroit is still here and it's still going up. If I ever start to feel bad about the future, I can go out, drive around, and see something beautiful and new out in the middle of nowhere. And I'll think to myself something like, “Boy, is that garden looking really nice… thank God somebody's out there and doing that.”

What legacy do you hope to leave?

I used to be a lawyer. I walked away from the law firm because I really wanted to do something useful in Detroit. I had this sense when my wife and I were having our first kid, that if I didn't play a role in the city's improvement, I was going to wind up being an old, grumpy dad — feeling like I hadn't made my contribution. Eventually, over time, as our unique strategy took shape, I came to realize maybe this is what I'm meant to be doing. So I guess the legacy I'd like to leave is simply that I helped Detroit become whatever it is trying to become.

Matthew Temkin

Greatwater Opportunity Capital